How did a boy raised in a small village in Barbados become one of the top United Nations officials tackling climate change?

In this episode of Awake at Night, Selwin Hart takes us on his inspiring life journey -- from growing up in a home without electricity to being at the centre of global negotiations to tackle the climate emergency.

The first person in his family to attend university, Selwin talks about the transformative power of education. He also explains how determination and a sense of community have served as driving forces in his career.

“If we give up, it means that my people in Barbados, my neighbors in the Caribbean, my friends in the Pacific, my friends in Africa, my friends in the developing world, and even folks in rich countries, we would seal their fate… So I refuse to give up.”

Transcript and multimedia

Melissa Fleming 0:05

From the United Nations, I'm Melissa Fleming and this is Awake At Night. Today, my guest is Selwin Hart, the Secretary General's Special Adviser on Climate Action, and Assistant Secretary General for the Climate Action Team. Selwin, we're going to get into your job a bit later - your big job - but first, tell me where you came from?

Selwin Hart 0:40

Thank you so much, Melissa, it's a pleasure to join you. I'm from a tiny island in the Caribbean, called Barbados, and an even tinier village in Barbados called Church Village or Chapel Land in Saint Phillip and that's where I'm from and this small rural village in Barbados has defined who I am. It gave me a sense of community, a sense of purpose and it helped to instil certain intrinsic values in me so...

Melissa Fleming 1:16

Close your eyes, describe what it looked like.

Selwin Hart 1:18

So when I grew up, in my earlier years, the roads were not paved, the countryside was dotted with sugarcane plantations. In fact, my grandmother worked on sugarcane plantations all her life, and my parents did so in their early days. Lots of fruit trees, gullies, lots of friends. What we lacked in material stuff, you know, we had in friendships and people. We were poor. But we honestly didn't feel as though we were poor.

Melissa Fleming 2:02

Because you had enough food to eat?

Selwin Hart 2:04

Yeah, enough food but you know, we lacked cars and we lacked... I remember, at my primary school, kids would come to school, and this was in the 70s and 80s, late 70s, and 80s in Barbados, kids would come to school without shoes, [they] were still going to school without shoes.

I remember, as a child, my parents didn't have electricity. My grandmother didn't have it either and I would read to her or I would read by the light of a kerosene lamp, so we lacked that stuff. But it as a child growing up, you never felt as though you were deprived of anything. B because you were surrounded by love, we were surrounded by love; the love of our parents, the love of our grandparents, the love of our families, and the love of our neighbours, and, you know, thinking about it now, you know, we would leave our homes unlocked whenever someone planted potatoes or yams or had limes. We all shared it as a village, or we shared it as a family so it's that sense of community that I miss most. It’s that sense of community that I remember most and that sense of community and love that has been a driving force in my life.

Melissa Fleming 3:37

Is it maybe because you didn't know what you were missing? Did you not see people who had those material things that kind of makes people strive in this consumer focused world?

Selwin Hart 3:53

Well, growing up back then, I did strive for things. Education was one of them and I was born in 1970 in Barbados, four years after Barbados became independent, and one of the first acts of an independent Barbados was to provide free education, free health care to its citizens and my generation was the first generation that truly benefited from access to education.

And while my parents and my grandparents did not have access to the same educational opportunities that my generation had, that I had and my brothers and my other relatives had, they nevertheless pushed us and pushed me in particular because I was one of the elders of the lot, to take full advantage of education, new educational opportunities that the new Barbados offered its citizens.

And quite frankly, not I can still hear my grandmother's voice telling me, you know, ‘One thing that can't take away from you is your education.’ It was not until I went into high school in Barbados secondary school that I was exposed to real material wealth. I went to primary school, [a] small, rural school with my neighbours and folks from other villages and at 11 years old, I did an exam, did well and I got into the top school on the island at the time Harrison College, and that school was in our capital city, Barbados.

So I was travelling from this very rural village in Barbados to the city on a daily basis and, you know, you saw kids coming to school in cars and with, you know, video games at the time, they’d started to come into... And, you know, it was then that I was introduced to real sort of material wealth, but the good thing is, you know, it was difficult. But the good thing is, I still remain very close to my village into my family and still retain those values that I had growing up.

Melissa Fleming 6:22

So you had to travel there, back and forth every day. On the bus or?

Selwin Hart 6:26

On the bus, on the bus. It's a small island so it would take probably about 45 minutes to an hour to travel to school and back on a daily basis.

Melissa Fleming 6:37

I mean, we're going to get to your work on climate action now but I can imagine, you know, growing up on a small island, surrounded by water and, you know, so much nature and nature being so important to the bounty of your family. What did nature mean to you growing up?

Selwin Hart 6:57

Nature was everything, you know, going to the beach and seeing over time and thinking back how coastal erosion happens. For example, when I was much younger, the coastlines stretched a bit further into the ocean. But we're also very close to the land as well and, and over the years, we've seen erratic seasons; longer periods of drought, sometimes excessive rainfall. But growing up, I was extremely close to the land, as I said, my grandmother worked on a sugarcane plantation for virtually all her life so from that perspective, always extreme because I never knew that I would get into climate [or] that this would be my calling.

Melissa Fleming 7:48

Did you mean, you said that you witnessed some change starting to happen but did you know what this was?

Selwin Hart 7:55

No, no, no, this was in the 1980s and at that time, climate was not a big issue. It was certainly not something that was discussed in any great detail in Barbados but you could see that the climate had and was changing, and that there were these signs in terms of how the ocean behaved.

Now, my grandmother, and my mother would often tell us about a hurricane that struck Barbados in the 1950s, before I was born, Hurricane Janet, and they would also tell me how their home was destroyed and how they had to live, basically, in a church for four weeks on end. So hurricanes were a present reality. I remember in the 1970s, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, we had a number of the other islands in the Caribbean, were struck by hurricanes. I think Dominica and some of the other smaller islands of the Caribbean and there was Gilbert in Jamaica.

But during that period, Barbados dodged many a bullet but the most visible sign back then was the ocean because we would go to the beach often. Sometimes once, twice a week. So we knew that there were some changes. We could see the impact of coastal coastal erosion. And we could see see the impacts of sea-level rise, but back then we didn't know what the cause, root cause, was.

Melissa Fleming 9:48

So it already was frightening, the prospect of a hurricane and the destructive power of one. I can imagine that this vision had some influence on how you imagine climate change affecting whole countries now, like your home country, Barbados. I mean, it's existential, isn't it?

Selwin Hart 10:15

It is, and the prospect and future that these countries face, it's a very bleak future. In 2019, I had what, I don't know how to describe it, but I visited the Bahamas after a really destructive hurricane and what I saw was truly a wake-up call for me. I've never seen destruction like that. It was a storm bomb and then this was weeks after, and it started cleanup. It was as if a bomb had been dropped on that island, and you're, you know, you're looking at the rubble and you're seeing people's lives. You're seeing papers, documents. You're seeing toys. You're seeing broken bicycles and cars were smashed.

And this climate crisis is different from many of the other crises that we're seeing and the bad thing is that it can wipe out entire communities and peoples and countries. But the good thing is, we still have time, I believe, to prevent the worst impacts by, of course, reducing global emissions. I don't want to get too wonky. But we also have time to protect people and protect livelihoods. You know, and when I saw those toys in the rubble on Abaco Island in the Bahamas, I said ‘No, we need to do different. We need to do right, by people who are on the frontlines of this climate crisis.’

Melissa Fleming 12:02

So it seems like there was this kind of personal recognition in you that you come from one of the most vulnerable countries in the world, and that you were going to be an advocate for the most vulnerable by doing this work. Is that a correct interpretation?

Selwin Hart 12:20

Well, to some extent, but I stumbled into climate almost by mistake. Do you want to hear?

Melissa Fleming 12:28

How did you get there? We kind of skipped forward but I mean, I didn't even... I mean, there was a point I read in your biography that you were in this school and your dad actually lost his job at one point, and I think your family went through quite a struggle. So what happened then and how did you get by?

Selwin Hart 12:46

I have so much respect, love and admiration for my parents. My dad died five years ago, and I think of him and I miss him every day. So I was in my final year of high school at Harrison College, and I'm the eldest of three, sorry, of four boys and my dad lost his job and this is a man who has worked all his life, he’s worked. And when I mean work, not, you know, sitting in an office, this is a guy who worked with his hands from the time he was like five years old. It was hard work.

I remember my dad cutting canes as a boy and my Mom would take us to the sugarcane fields to give him lunch. Eventually, he got this job where he worked for a power company and, you know, it was hard stuff. It was back in those days with poles and running wires and just very dangerous as well.

Melissa Fleming 13:51

And he never complained?

Selwin Hart 13:53

He never complained. You know, he wasn't the type of man back then to be constantly giving you hugs and saying how much he loved you but he was one of those, you know, he was a provider and that was his role. He saw himself as a provider. So him losing his job was a major blow for him and I was finishing high school. And I had my eyes set on going to university, applied for university and got into the University of the West Indies in Barbados. But I had to do it part-time. I had to find a job to help support my family and eventually he got back on his feet a few years later.

But that was a very difficult period because I was very disillusioned; all my colleagues and friends at school, you know, they were able to go to university full time. Some went to universities overseas. But, to me, I would not, now thinking back, I would not trade that experience for anything. Of course, it was unfortunate that my dad lost his job but having to work full time and go to university, it really helped to build character. And I also met some really, really, really, really, really, really great people as well.

Melissa Fleming 15:17

What kind of work were you doing?

Selwin Hart 15:19

I was an immigration officer and it's a funny story. Funny story, Melissa, so I walk into this interview and, and this lady sees my resume. She says, ‘Young man, why aren't you going to university?’ Her name was Mrs. Cook. I said ‘Yeah, I was going to get to that….’ I said ‘Yes. I'll be honest with you. I've applied to university, I've been accepted. But I need to work. I need this job. I promise you that if you give me this job, and you give me the time to go to university, I will put the time back in.’ And, you know, she was an old school teacher who would become like a Deputy Chief Immigration Officer and we're still friends up until this day. And Mrs. Cook said, ‘Okay.’ So I walked...I said, ‘You know, I'm not gonna get this job.’ Because, you know, it was ideal. It was a government job. It would provide me with security, give me good hours as well. And I got home, [I] took the bus back home and when I got home, my Mom said, ‘Selwin, you just got a call from immigration. They told you to report to work on Monday.’

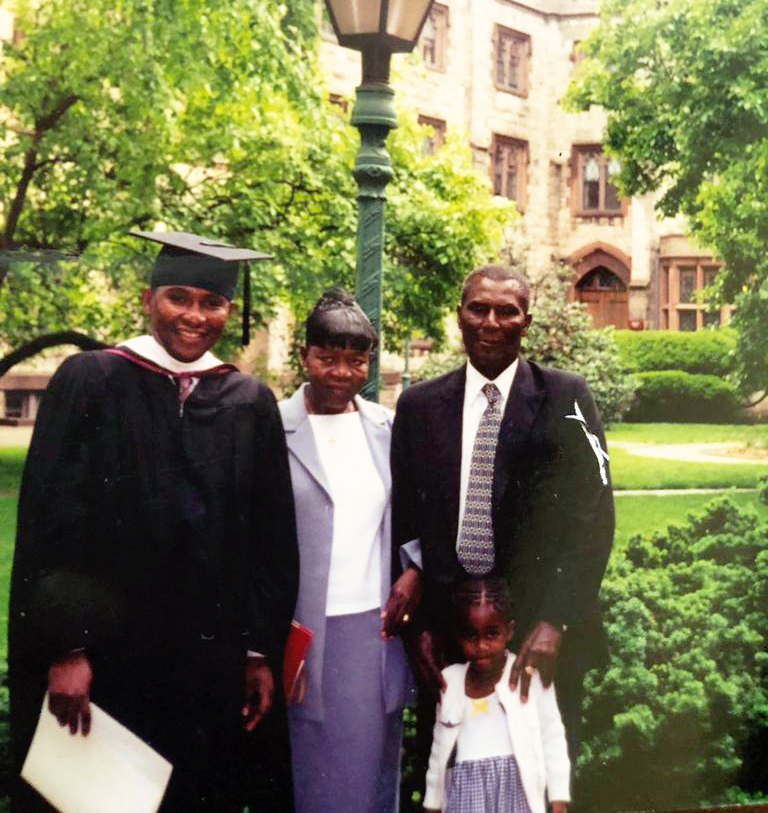

When I went in she said, ‘Selwin, I was touched by your story. I called a few people. They verified everything that you said,’ and, you know, for four years, she allowed me to go to university part-time and I put the hours back in. I would work late. I would sometimes come in on Saturdays and that allowed me to get through university and get my first degree. And I remember after I got my degree, she was mad at me because I didn't go to graduation, the official graduation, and she was so mad at me for depriving my parents of that opportunity because I was the first in my family to get a university degree.

She asked me after I got my degree, I then got a somewhat of an offer of interest to go and work at our Ministry of Finance and Economic Affairs and she asked me to stay a few more months to help her with a computerisation project and, you know, I could have gone but she was so good to me that I stayed. I stayed and as a result of that, then the Foreign Ministry had some vacancies and so I got into the Barbados Foreign Service. So, you know, Mrs. Cook, she's one of those people.

Melissa Fleming 18:08

So you were the first one in your family to go to university and then you made it even to the Foreign Ministry. I can imagine your parents and Mrs. Cook were very proud of you?

Selwin Hart 18:19

They were proud and the thing is, we never... because we came from such humble means, I never really knew what the possibilities were, right? I never thought I'd be sitting here as Assistant Secretary-General, being interviewed by you, Melissa. We never knew, you know, I never knew and they definitely did not know what the possibilities were and and I think that's good because it meant that you know, I just roll with the tide. I just try to do my best. I tried my best to represent my country. I took chances that you know, possibly if I knew what was at stake, I probably wouldn't have taken...

Melissa Fleming 19:23

Sometimes it’s best not to know exactly what could be waiting you but now you know a lot about what could be waiting the world if the world doesn't take climate action, but just how did you get to the United Nations? How did you manage to go from Barbados to being in an international role?

Selwin Hart 19:43

Okay, so, um, I was posted to New York at our consulate. That was my first post and when I got to New York, I decided, you know, I need to do a Master’s. I need to do my Master’s so after I got my Master’s, there was an opening at the Barbados mission to the UN a few years after. And given that I was already in New York, my superiors at the Foreign Ministry decided, you know, why not give Selwin a chance and I was transferred over to our Mission to the United Nations. And I started to negotiate second committee issues, of which climate was one of them.

Melissa Fleming 20:30

So that was your introduction to climate…

Selwin Hart

That was my…

Melissa Fleming

And was there a kind of ‘Aha!’ moment, this is what I'm passionate about or…?

Selwin Hart 20:37

Almost immediately. So one of the first big climate related negotiations that I had was the preparation for the 10 year review of the Barbados programme of action. So 2000, around 2003-4, the 10-year review of the Barbados programme of action, so it was a massive negotiation around the programme of action for the small island developing states.

Melissa Fleming 21:09

So if you talking about...just how do you picture, how can you just describe in pictures, what this jeopardising of survival means in real terms. Like what is the threat for small island developing countries?

Selwin Hart 21:24

Well, it depends on where you are, if you're in the Pacific, and it means that rising sea levels could... rise in seas will wash away your homeland, your ancestral home. You will lose, you can lose your entire country or your national heritage. If you're in the Pacific or the Caribbean or in the Indian Ocean, one storm, one hurricane can reverse decades of development gains, alright? So it's, it's a threat that changed your life, changes the development trajectory of your country, virtually overnight?

Melissa Fleming 22:06

What is it that really right now is keeping you awake at night, when it comes to climate change?

Selwin Hart 22:14

What keeps me up awake at night? The slow pace of the response. What is still shocking to me is that we know. We can't claim ignorance or uncertainty about what is happening on climate. But yet, we're not doing enough, right? And, as Martin Luther King, Jr. said, ‘There's a thing as being too late.’ Right? And that's what keeps me up at night that, you know, we are just going to be too late.

Melissa Fleming 23:05

What keeps you going then, not being too late I guess. Trying to keep up?

Selwin Hart 23:11

So what keeps me going is we still have an opportunity, we still have an opportunity, and what also keeps me going is that you know, if we give up, it means that my people in Barbados, my neighbours in the Caribbean, my friends in the Pacific, my friends in Africa, my friends in the developing world and even folks in rich countries, we would seal their fate, right? We will seal their fate if we give up now. It means that some will face an uncertain future and some will have no future. We cannot and we just cannot give up. So I refuse to give up.

And I think as The UN, we have to continue to speak truth to power. I don't want to get too wonky or to flood you with stats but last year alone 30 million persons were displaced from climate and extreme weather events. Three times as much as those who were displaced as a result of war and violence. So this climate...

Melissa Fleming 24:41

It’s happening. These are happening more frequently and they're more devastating. The Executive Director of the World Food Programme was recently in Madagascar and he witnessed a horrific drought, which he said was very much linked to climate change there. Can you describe what's happening in Madagascar and how climate change is affecting [it]?

Selwin Hart 25:08

We are seeing, across the world and in Madagascar and in other places, we're seeing climate exacerbate already existing threats and challenges. So one of the, I would say underreported, facts of the recent report from the IPCC was that the impacts of climate change are going to be unevenly distributed across the world. Even if we were to hold the increase in global average temperature to 1.5. That's a global average. We will have much higher levels of warming in Africa. We're going to see higher rates of sea-level rise around the African coastline. So the impacts in Africa will be far more severe, and we're already seeing this, far more severe than in other parts of the world. So what we are seeing in Madagascar, it will just get worse, unfortunately, and it will be amplified, unfortunately, across the continent.

Melissa Fleming 26:33

It sounds like you're really frustrated.

Selwin Hart 26:37

Frustrating, but determined, right? Frustrating but determined. There’s this sufficient, you know, I use this term political will, which I don't always like, but extremely frustrating, but very, very determined and we can turn the tide, right? We can turn the tide. So while it is frustrating, you know, we just have to continue, I believe, as The UN to speak that uncomfortable and inconvenient truth. In his closing statement to COP26, the SG (Secretary General) called on the entire world to go into emergency mode and every institution, every country needs to go into emergency mode to tackle this crisis.

Melissa Fleming 27:33

I've been looking at the disinformation around climate change, thinking that it kind of had maybe moved to COVID but no, it's still very much alive and kicking. And they're actors out there who want to mislead the public and to play down climate, maybe not deny it as much anymore, but play it down or, you know, make people feel confused or not think it says urgent. How does this make you feel because information is just so important?

Selwin Hart 28:10

We're at a stage now where we have to use every weapon at our disposal to counter disinformation and misinformation. We know who some of these players are, right? It's the traditional ones, not sure if I can say, but [the] fossil fuel industry has been behind for decades a lot of the misinformation and disinformation around climate change and, quite frankly, we need to be a lot stronger in terms of countering some of the the efforts of their lobbyists. We also know that, for example, some companies who are touting themselves, as climate champions, are also involved in negative lobbying against ambitious climate legislation or policies or actions in some of the key countries.

Melissa Fleming 29:20

So what would you say to them?

Selwin Hart 29:23

[It] would be: ‘Stop it,’ for one. But we also... and our friends and civil society need to call them out on it as well.

Melissa Fleming 29:32

Is there anything that you're hopeful about?

Pleasure discussing #COP26 outcomes & #ClimateAction priorities at the RCs meeting. In tackling the climate emergency, @UN country offices are uniquely placed to harness the Organization's convening power to unite stakeholders & its expertise to help countries give life to NDCs. pic.twitter.com/uwiptGCov0

— Selwin Hart (@SelwinHart) December 13, 2021

Selwin Hart 29:36

Yeah, I'm hopeful that we can solve this crisis and, it’s not, I say this all the time to my colleagues, it's not Island optimism but my life and the life of my parents and my grandmother, in particular, she would always say ‘Where there's a will, there's away,’ right? And that always, that has always stuck with me. And I think that, despite this concern over, you know, lack of urgency, lack of ambition, we're not moving fast enough, we're not moving at scale.

There are rays of hope. I see, honestly positive rays of hope, you know, when I look at the Glasgow outcomes, things that I never thought would be in a COP decision are there. The fact that there is now this almost international consensus around the 1.5 degree goal of the Paris Agreement, you know, and Melissa, I was a climate negotiator for the islands back in 2008. When we first put the 1.5 degree goal of the Paris Agreement on the table, the only other group that supported us was the least developed countries.

All of the big guys told us it's unrealistic. It's impossible, non starter, and now in Glasgow to see it, you know, firmly embedded as the objective for global ambition gives me hope, you know, it's just words on a paper, but it gives me hope. It gives me hope that despite years of disappointment, despite all the setbacks, there is a path forward. You know, because if we were to give up hope, then as I said earlier, it would mean that we would give up on the people in Barbados, in Bangladesh, in Costa Rica, in Niger, and we can't. We just can’t. We just can’t.

Melissa Fleming 31:58

Selwin Hart, thank you so much for joining us on Awake At Night.

Selwin Hart 32:02

Thank you so much, Melissa, thank you.

Melissa Fleming 32:03

Thank you for listening to Awake At Night. We'll be back soon with more incredible and inspiring stories from people working to do some good in this world at a time of global crisis. To find out more about the series and the extraordinary people featured, do visit un.org/awake-at-night

On Twitter, we're @UN and I'm @melissafleming. Selwin is @selwinhart. Subscribe to Awake At Night wherever you get your podcasts and please take the time to rate and review us. It does make a difference.

Thanks to my producers Bethany Bell, and the team at Chalk & Blade: Laura Sheeter, Cheri Percy, Fatuma Khaireh, and to my colleagues at the UN: Roberta Politi, Darrin Farrant, Tulin Battikhi, Bissera Kostova and the team at the UN studio.

The original music for this podcast was written and performed by Nadine Shah, and produced by Ben Hillier. The sound design and additional music was by Pascal Wyse.